Recommended Insights

I’ve always been drawn to liminal spaces and architectural walkthroughs, but turning that interest into something real and shareable has been harder than I expected. This post documents what happened when I tried to teach AI to reconstruct a real house from sparse images and deploy it as a walkable 3D scene on the web, and what broke once the system started “almost” working.

(If you’re looking for the full technical write-up, you find it here: https://schusterian.notion.site/How-Automatable-Is-3D-Environment-Reconstruction-from-Sparse-Images-Today-2e1488886d578064b91ceede58adccc6?source=copy_link. If you’d like to see the website with these iterations, you can find it here: https://creepy-building-blender-automated.vercel.app/. This post is about the experience of doing this and what I learned by actually trying it.)

I’ve spent a lot of the last year watching liminal and near-liminal space videos on YouTube, and seeing similar kinds of environments show up in games. There’s something about these quiet, mostly empty spaces that feels calming to me, but also slightly unsettling in a way that keeps my attention. They’re familiar enough that you recognize them immediately, but empty enough that your brain starts filling in what should be there. At some point, I realized that I don’t just want to watch these spaces, I want to make my own.

I’ve used Blender in the past as a creative outlet, and I’ve always enjoyed it. I don’t know if I was ever particularly good at it, but I liked the process of building things and seeing them rendered on the screen. The difference this time is that I wasn’t interested in creating 3D objects in isolation. If I was going to spend time on this again, I wanted the result to be something you could actually move through.

That’s where the web comes in. A Blender file is only interesting to someone who already has Blender and knows how to use it. A website with a URL is something anyone can click on and explore. I’ve had projects that took a lot of effort to get working locally and people were mostly indifferent to them, and then I put essentially the same thing behind a link and suddenly people were far more engaged. In a way, it became real to them. That’s the experience I wanted.

At the same time, I’d been watching AI tooling move faster than I expected. Claude Code, in particular, had already surprised me in a lot of ways. It can build applications, refactor code, and orchestrate workflows in a way that feels genuinely useful. When I came across Blender MCP (link here: https://github.com/ahujasid/blender-mcp), which allows Claude to directly control Blender, it felt like we could build something cheaply. If AI could already reason about images and coordinate tools, maybe it could help lower the activation energy required to create walkable 3D spaces.

I didn’t approach this from the perspective of deciding whether AI can or can’t do this in some abstract sense. I’ve never found that line of thinking very helpful. What I’ve learned is that you only really understand a tool by picking a concrete problem and forcing it to work through it. Optimists assume things are solved before they are. Pessimists find a breaking point and stop there. Neither tells you much about what’s actually possible.

So that’s what I did here. I picked a very specific, very constrained problem and tried to work it all the way through. Instead of starting with a whole liminal world, I chose a single real house, one I’ve driven past many times, and tried to build a workflow where AI could reconstruct it from sparse reference imagery and turn it into a walkable 3D space in the browser. The goal wasn’t to produce a perfect asset, but to understand how far this kind of workflow can actually go today, and where it breaks down when you try to make it real.

Originally, my idea was to create a lane with multiple houses and maybe some surrounding environment. But whenever a big project keeps failing, the right move is almost always to narrow the scope.

In this case, narrowing the scope meant picking a single house.

Anything smaller than that stops being the same problem. A single room is a different challenge. A single object is a different challenge. A house felt like the smallest unit that still captured everything I cared about: exterior structure, interior layout, proportions, and the feeling of moving through a real place.

I chose a specific house that I’ve driven past many times. It’s a slightly eerie building on the side of the road, and for whatever reason it stuck with me. I’ve even had dreams where I’m inside it, which is probably not something you normally admit in a technical blog post, but it’s true. It also happened to have decent Google Maps coverage on the front and sides, which made it a practical choice.

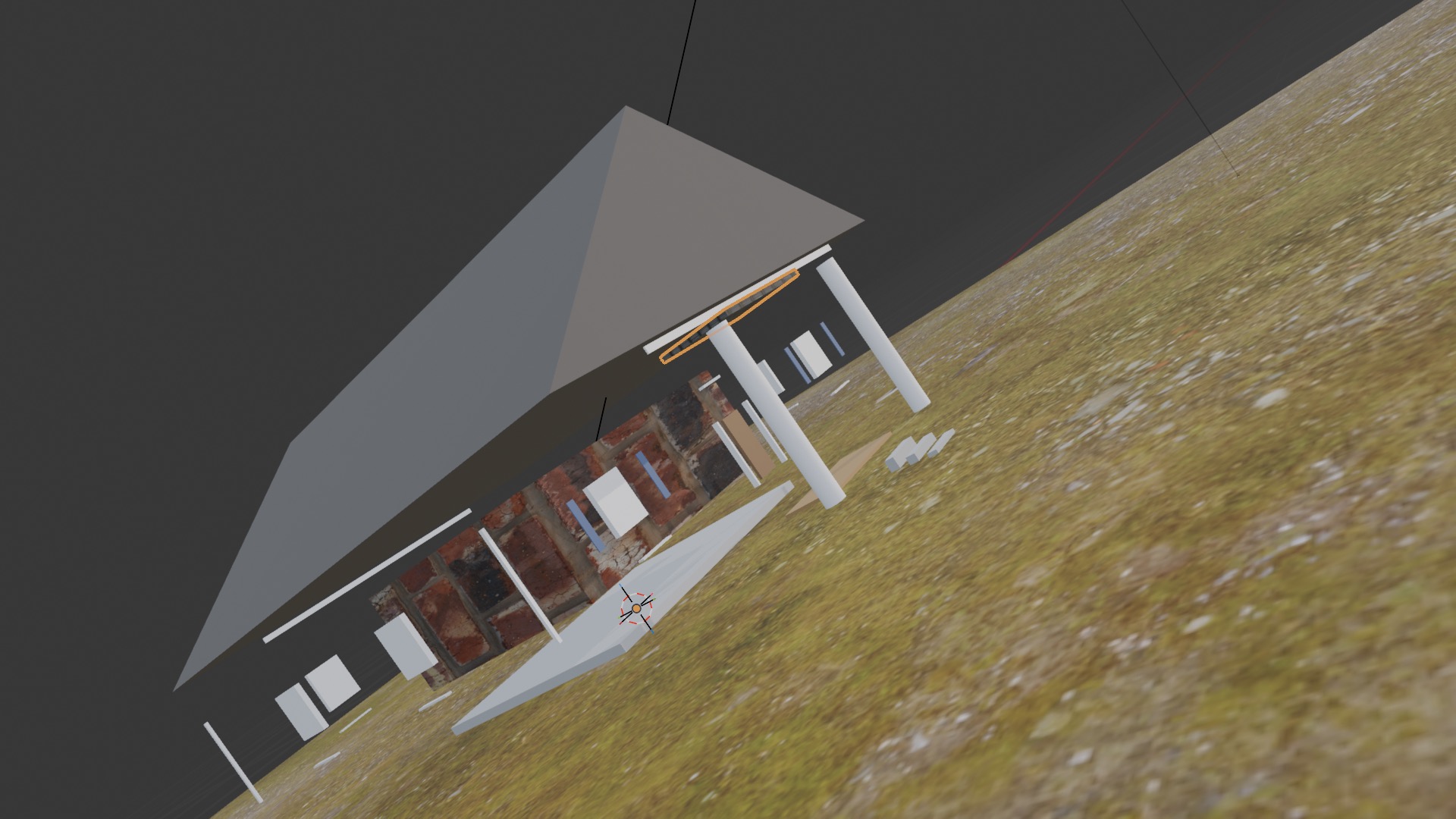

Early on, I assumed this would be relatively straightforward. I got Blender MCP running, connected Claude Code, and started trying to describe scenes and have it build them.

At first, it felt promising. It could create a plane, create a road, and sort of generate hills. The proportions were off, but that wasn’t surprising.

The real issue came up when I attempted to describe the house and what it should look like. At first, I wasn’t expecting it to look perfect, I was hoping the shape would at least be roughly correct. It wasn’t.

The roof floated. Windows were misplaced or missing entirely. It would confidently report that it had created a house, and then you’d look at the viewport and it was clearly wrong. After an hour of trying, it still couldn’t reliably place windows. It could talk about what it should do, but it couldn’t consistently translate that into geometry inside Blender.

I also tried switching approaches and building simple structures in code outside of Blender to see if that helped. While I could make some progress, I kept running into the same core issue: the model could reason about structure in language, but it didn’t have the context needed to build coherent 3D objects without a lot of scaffolding.

That’s when it became clear this wasn’t a prompting problem. It was a workflow problem.

When an LLM creates a landing page, it benefits from an enormous amount of implicit structure. It has seen millions of examples. It understands conventions and order of operations.

With Blender, none of that context exists in a usable way. The model can describe architectural concepts, but it doesn’t know how to apply them inside a 3D tool unless you give it a structure to work within.

On top of that, without determinism, progress kept getting overwritten. Fixes would regress. Improvements in one area would break another.

So I had to impose structure. The workflow eventually became something like: analyze the reference images, talk through what’s there, generate a deterministic specification with explicit coordinates, execute that in Blender, validate it, and then repeat in a way where each change actually stuck.

That ended up being the real work of the project.

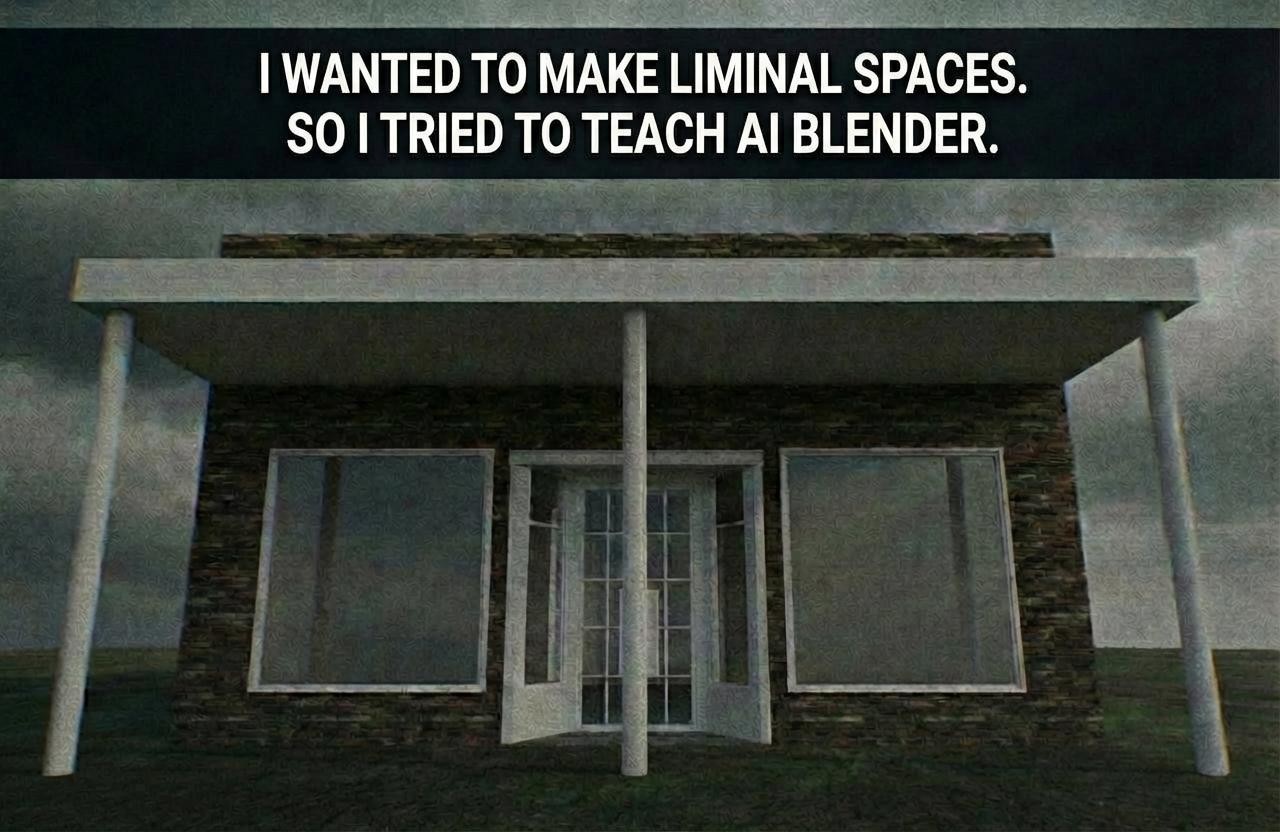

Once that structure was in place, progress became possible. The first few iterations were rough, but then the model started getting the broad strokes right. The house began to resemble the real thing.

That middle state turned out to be the most dangerous part of the process, because it creates momentum without actually resolving the hardest problems. You can see the path forward, and it’s tempting to assume the hard part is over.

But the reality was that fine-grained detail kept breaking down. Window trim, subtle geometry, small cues that make a structure feel real were consistently missed. My instinct was to keep pushing on the details until it was correct, but with the current approach that became prohibitively time-consuming. To move forward, I had to sacrifice detail in order to get to done.

Once something was correct and encoded into the spec, it often stayed correct going forward. Not always, but enough to build on. For the first 20 or so iterations, I was able to make progress before everything started to slow down. We were getting closer to a workable product, but something was missing.

What became clear over time is that generation wasn’t the main bottleneck. Evaluation was.

Claude could infer the broad structure of the house, but it struggled to notice small errors that a human would catch instantly. If the system can’t reliably see mistakes, it can’t reliably fix them.

After looking around, this seems to be a broader open problem. You can buy better mesh generation. You can buy better texturing. But automated visual validation and critique loops are still weak, especially at the level of detail needed for convincing spaces.

That’s where this process started to falter. To fix that during this process, I was effectively the ‘eyes’ for the system. So this meant that for some iterations, the changes were literally just moving an object .2 meters north. For every phase of development, it would get the broad details right and need a lot of help in getting to the finish line. Often at this point, it felt like I could do it by hand faster.

Even with those limitations, AI contributed something real. It lowered the barrier to entry. It made iteration possible without deep Blender expertise. It acted as an orchestrator that kept the process moving.

Even if Blender MCP isn’t the final form of this, it feels clear to me that tools like Claude Code are going to sit at the center of creative workflows like this, coordinating tools and structure rather than replacing human judgment.

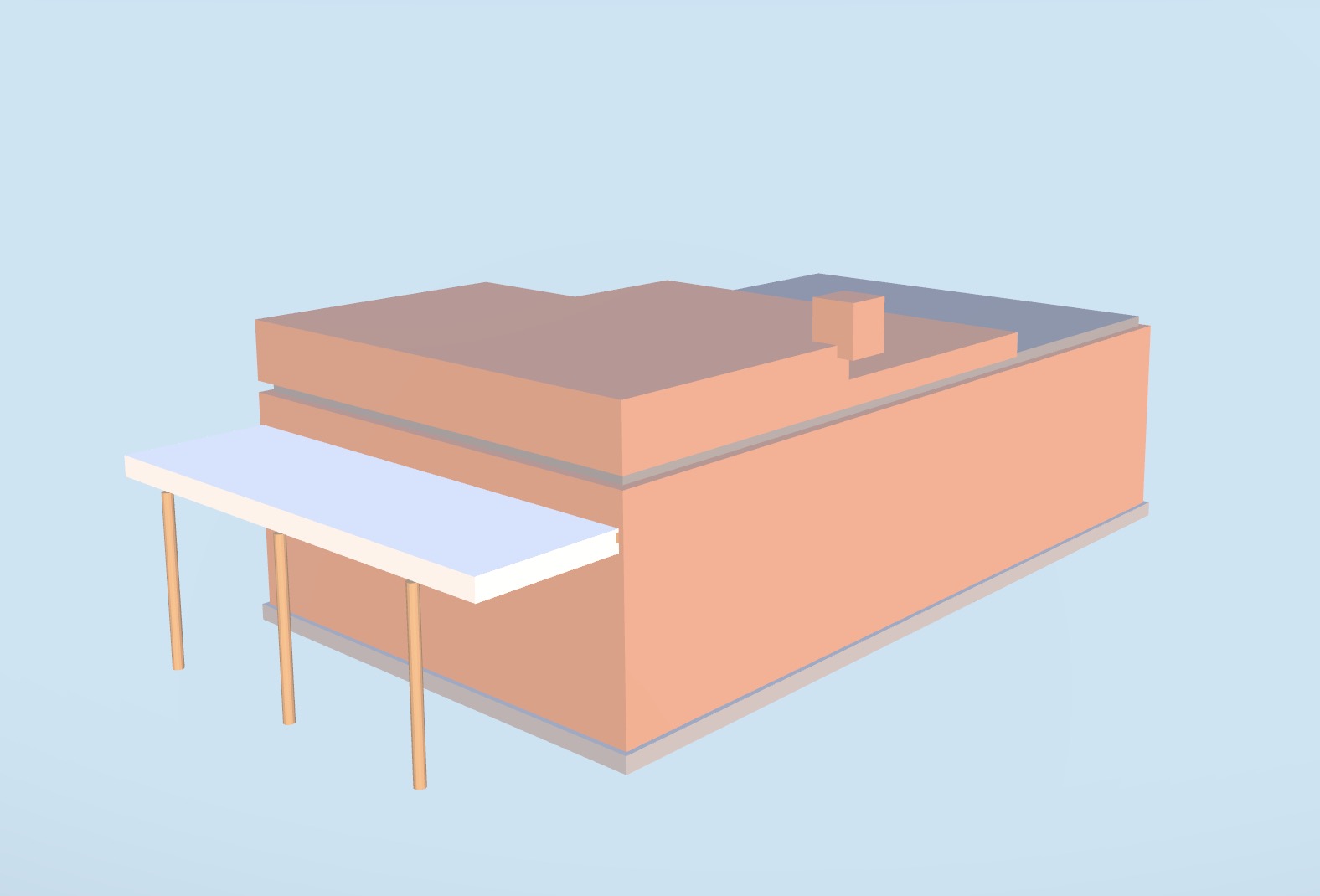

Once the mesh itself was in a place I was reasonably happy with, most of the remaining time in the project went into getting some basic texturing applied and then putting the structure into a minimal environment that could be rendered in Three.js. Compared to the amount of effort spent getting the geometry right, this part was intentionally much lighter.

Roughly speaking, I probably spent about 15% of my total time on texturing, and maybe another 5% on the surrounding environment. You’ve probably already noticed that the textures look okay-ish and that the environment itself doesn’t look particularly realistic. That wasn’t an accident. At some point, I made a conscious decision to ship what I had rather than keep polishing indefinitely, and this was the level I could reasonably ship at.

With textures specifically, if I had spent the same amount of time on them as I did on the mesh, it’s very likely the result would look meaningfully better. I also realized after the fact that there are some fairly capable AI-driven texturing tools that I simply didn’t know existed at the time. If I were to do this again, I’d almost certainly have Claude orchestrate texture application using one of those tools instead of relying on the more manual approach I took here. Even so, it became clear that with stronger texturing knowledge, this could already be pushed further without changing the rest of the workflow.

As for the environment, my goal there was much simpler. I just wanted the space to be walkable, and that goal was met. If I wanted the environment to feel realistic, I’d need to spend a lot more time understanding lighting, scene composition, and how subtle environmental cues influence perception. That’s less about AI limitations and more about my own gaps in knowledge. With better understanding of lighting and environmental design, I could have taken this further, even with the same tools.

One thing that did stand out is how easy the Three.js side of this was by comparison. Claude essentially one-shotted the initial Three.js implementation when I asked it to create a basic walkable scene. Every iteration after that was straightforward and low-friction. From a web development perspective, this part felt almost trivial. I was able to deploy the scene to Vercel very quickly, and it just worked.

For web-oriented tasks, Claude’s code generation is genuinely impressive. If you build CRUD applications for a living, I’d probably be paying close attention right now. For my purposes, it meant that once the 3D asset existed, getting it into a shareable, browser-based experience was one of the least painful parts of the entire project.

If anything, I feel more optimistic after doing this project. While it isn’t a push-button solution, Claude has a lot of levers to pull that allow someone to create an interesting solution.

Of the problems, I encountered, most of them are either solvable with a better approach or there’s better tools for the job. Orchestration and parallelism feel like problems that are trending toward being solved. AI textures have evolved a great deal and have easy and cheaply priced APIs that help with the solution.

The part that really stands out as unsolved is visual validation, teaching systems to actually see and critique fine detail. When I asked my AI friends for feedback (some with over a decade of experience), that’s the area they pointed me to. And when I went further to find what solutions could solve this… turns out there aren’t any. This is an unsolved problem.

Ultimately, what I want is simple to say and hard to build: take a random photo off the internet, answer a few questions, and generate a walkable 3D scene the way we generate landing pages today.

That would be incredibly powerful.